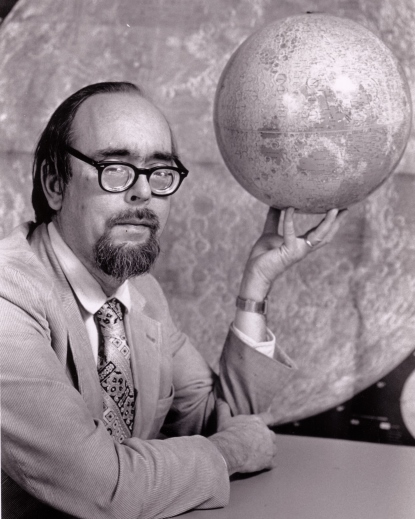

Von R. Eshleman died peacefully on September 22, 2017, five days after his 93rd birthday. Although he began his career in radar astronomy, he is best known as a pioneer in the use of spacecraft radio signals for precise measurements in planetary exploration — specifically, the radio occultation method for profiling planetary atmospheres and ionospheres, which has now been “brought home” for monitoring Earth’s atmosphere using GPS satellites.

Von R. Eshleman died peacefully on September 22, 2017, five days after his 93rd birthday. Although he began his career in radar astronomy, he is best known as a pioneer in the use of spacecraft radio signals for precise measurements in planetary exploration — specifically, the radio occultation method for profiling planetary atmospheres and ionospheres, which has now been “brought home” for monitoring Earth’s atmosphere using GPS satellites.

Von was the youngest of four boys born in Covington, Ohio, a farming community with a large population of Old German Baptist Brethren, from which his grandfather had broken away in the late 1800s. He progressed rapidly through his early school years, then served as an electronics technician in the U.S. Navy during World War II (1943-46). While stationed in Italy at the end of the war, he became intrigued by the possibility of bouncing radio signals from the lunar surface. Although his own ship-based experiments were unsuccessful, this curiosity guided his professional life for the next 60 years.

He attended the General Motors Institute of Technology and Ohio State University before graduating with a bachelor’s degree in electrical engineering from George Washington University in 1949. While at GWU, he met and married Patricia Middleton and they had the first of four children. Recruited to graduate school at Stanford University by Fred Terman, he obtained an MS in 1950 and a Ph.D. in 1952. His doctoral research, supervised by Mike Villard and Larry Manning, was on radio reflections from ionized meteor trails in the upper Earth’s atmosphere.

After serving five years as a member of Stanford’s Electrical Engineering research staff, Von was promoted to Assistant Professor in 1957, then Associate Professor, and finally full Professor in 1962. With colleagues Allen Peterson and Ray Leadabrand, he founded the Stanford Center for Radar Astronomy in 1962, which oversaw two-way dual-frequency radio propagation experiments between Stanford’s 150-foot antenna (‘The Dish’) and Pioneers 6-9 in orbit around the Sun, measuring the density, velocity, and structure of the solar wind.

By the mid-1960s Eshleman’s team had refocused on planets and on the telecommunications signals normally used to transmit spacecraft images and other remotely acquired data. The radio signals themselves are perturbed when a spacecraft flies behind a planet; by measuring the small changes in frequency, it is possible to determine the temperature and pressure profile of an occulting atmosphere (very similar to the results returned by a weather balloon) and the electron density of an ionosphere. The experiments were originally proposed for an ‘uplink’ geometry (transmission from Earth to the spacecraft), but only ‘downlink’ implementations were approved. Nonetheless, graduate students Gunnar Fjeldbo and Len Tyler (among others) perfected the technique and were rewarded with the first profiles from Mars (cold and thin) and Venus (hot and dense) in 1965 and 1967, respectively. Eshleman and his associates also demonstrated that properties of planetary surfaces could be derived from radio echoes reflected from the Moon and Mars.

Eshleman was not involved in Pioneer 10 and 11 radio occultation experiments at Jupiter until it became apparent that the radio results differed radically from results obtained by other instruments. Over several years, Von and others worked out the corrections needed for analysis when planets are oblate (as the gas giants are because of their rapid rotation). The effects of turbulence and magnetic fields were incorporated by Bjarne Haugstad and Dave Hinson. Von led the Radio Science Team through the very successful Voyager 1 and 2 planning, implementation, and Jupiter encounters, then handed off day-to-day operations to Tyler.

After Voyager, Eshleman focused on topics such as evolute flashes during deep radio occultations, stellar gravitational lenses and their effects on propagating radio waves, ring particle dynamics, absorption in planetary atmospheres (with students Paul Steffes and Tom Spilker), and retro-reflection from icy planetary surfaces. Although not a member of the science team, he got to see the ultimate radio occultation experiment (an uplink implementation) when New Horizons passed Pluto and signals transmitted from Earth were perturbed by its barely detectable atmosphere.

Dozens of graduate students benefited from Von’s direct mentoring; but he was also an innovative classroom teacher. He converted a mezzanine-level class on electromagnetics to a generalized “waves” class for a broader audience of Stanford graduate students — such as those interested in acoustics, seismology, and oceanography. For advanced undergraduates, he developed a new class called “Planetary Exploration”, which was attractive to students with science, engineering, and mathematics skills but who were not majoring in astronomy.

Von maintained contacts with industry, serving as a consultant for North American Rockwell and Watkins-Johnson. He advised the McGraw-Hill Book Company, the National Bureau of Standards, and (of course) the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. He also served briefly as Deputy Director of the Office of Technology Policy and Space Affairs in the U.S. Department of State. But he always returned to the skilled and productive use of electromagnetics to explore the universe — a task that his associates recall that he not only wanted to do, but to do well.

Richard Simpson and other colleagues

Von R. Eshleman died peacefully on September 22, 2017, five days after his 93rd birthday. Although he began his career in radar astronomy, he is best known as a pioneer in the use of spacecraft radio signals for precise measurements in planetary exploration — specifically, the radio occultation method for profiling planetary atmospheres and ionospheres, which has now been “brought home” for monitoring Earth’s atmosphere using GPS satellites.

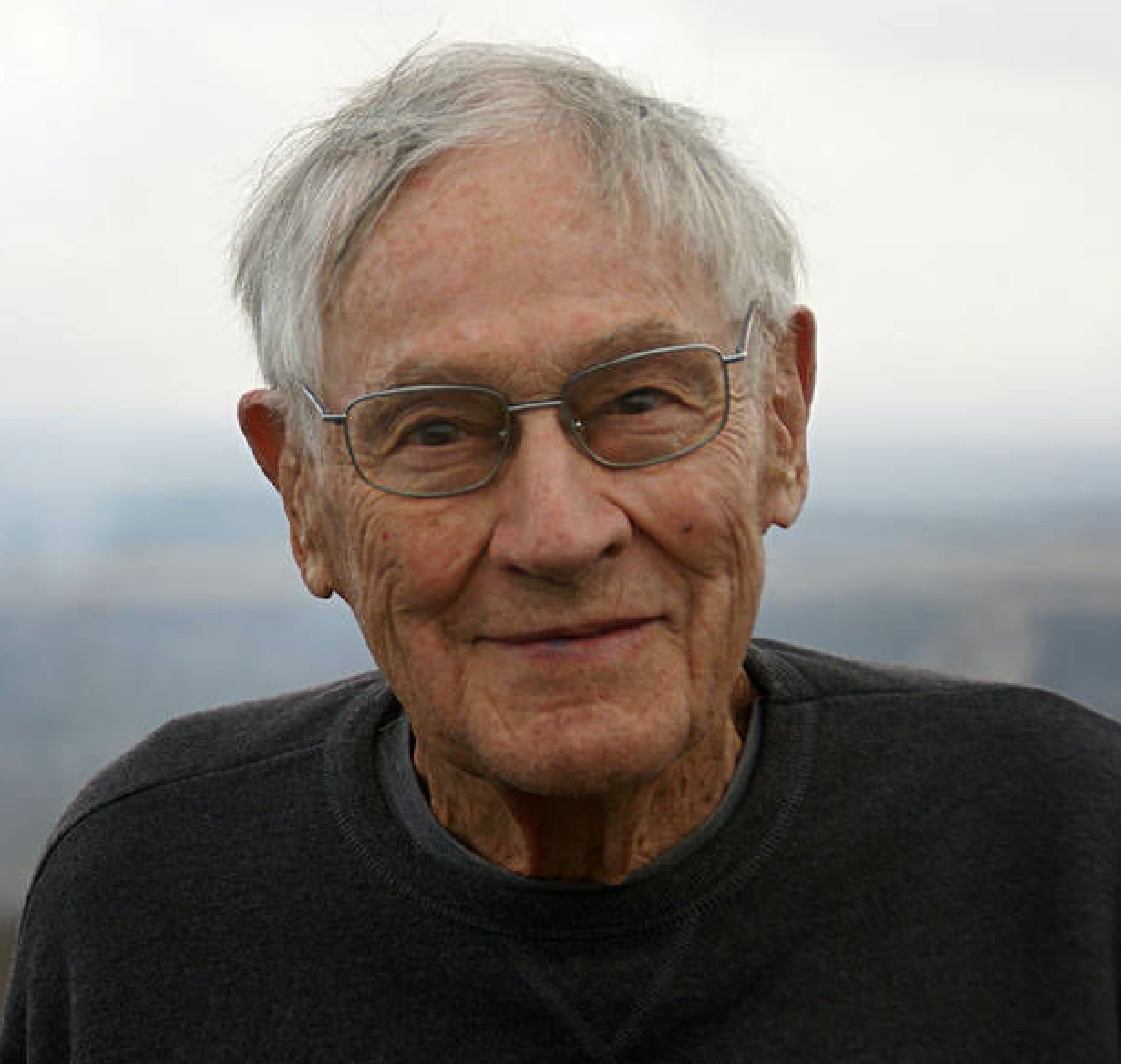

Von R. Eshleman died peacefully on September 22, 2017, five days after his 93rd birthday. Although he began his career in radar astronomy, he is best known as a pioneer in the use of spacecraft radio signals for precise measurements in planetary exploration — specifically, the radio occultation method for profiling planetary atmospheres and ionospheres, which has now been “brought home” for monitoring Earth’s atmosphere using GPS satellites. Nathan Bridges, a planetary research scientist at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL), died on April 26. He was 50 years old.

Nathan Bridges, a planetary research scientist at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL), died on April 26. He was 50 years old.